(Just found the Exploratorium posted the pdf catalog (including my essay) for Tim's 2015 installation online...)

"What the heck is a bosun’s whistle? OK, something’s coming back—a deep childhood memory of strongly desiring and eventually obtaining a Cap’n Crunch plastic two-note whistle from the bottom of a cereal box. I was an experimental musician even then, and explored the humble instrument’s potentials extensively around the family home for several weeks, before it mysteriously vanished. I was inconsolable. But I got over it and moved on to the family turntable, which is a whole other story.

When Tim Hawkinson decided to use a bosun’s whistle as the model for his ambitious kinetic sound-sculptural installation at the Exploratorium, he was tapping into a curious nexus of pop cultural and historical reference—an auditory trope that most of us would recognize, but whose original meaning and function are probably lost in the fog of technological obsolescence.

Familiar through countless mass-media depictions of nautical life (and, as I recently noticed, extraterrestrial escapades in the form of the Starship Enterprise’s electronic PA system on the original Star Trek series), the harsh, teakettle tones of the non-diaphragm type whistle have a loose semiotic charge—navy-something—but very few parsable details.

In fact, although it is now limited to ceremonial use—an idiosyncratic vestigial indicator of a “traditional” identity which has been completely subsumed by a homogenized global military culture centered on computers—the bosun’s pipe (aka whistle, call, or pippity-dippity) represents a functional language devoid of words; resembling whistlelanguages found in indigenous cultures around the world and probably inspired and based on some ancient maritime culture—the Greeks supposedly used pipes to time the oar-strokes of their galley slaves.

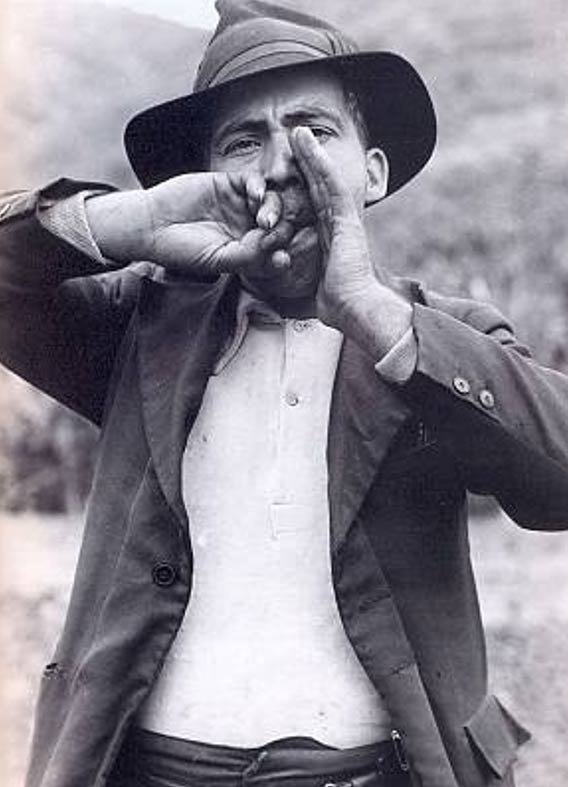

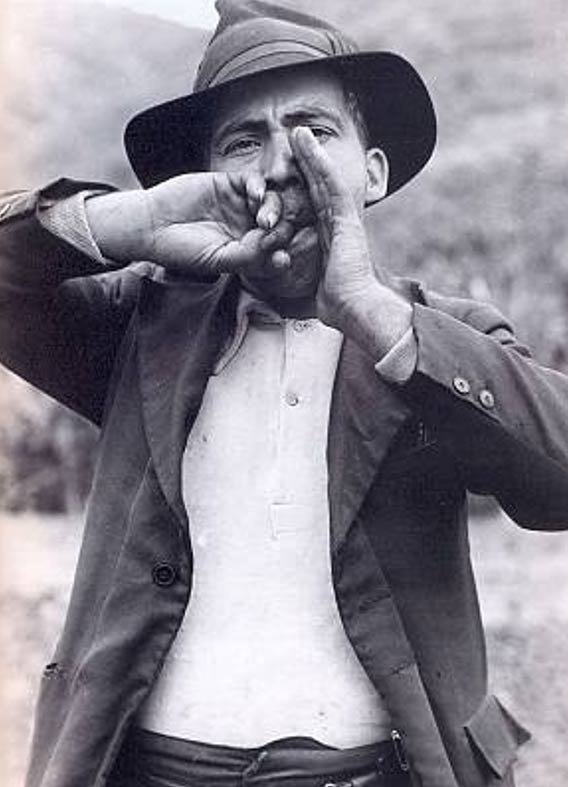

While a traditional whistled language such as Silbo Gomero—used by inhabitants of the Canary Islands to communicate across their jagged terrain—bears a direct, if convoluted relationship to the regular spoken language of its host region, the same cannot be said with any certainty about the language of the bosun’s call. Instead, seamen have, over the course of time, reverse engineered the whistles with phoneme substitutes of their own devising, nonsense phrases or ironic vernacular translations, such as “The officers’ wives eat pudding and pies, the sailors’ wives eat skilly” for the officers’ call to mess (dinner).

There’s something about this inversion and simulation of an organic communication system—and the improvisational, collaged translation that unfolds from it—that seems very reminiscent of Tim Hawkinson’s creative process. On an immediate level, the bosun’s whistle dovetails with a number of recurring themes in Hawkinson’s oeuvre..."

Read or download the entire pdf catalog for Tim Hawkinson's "Bosun's Bass" at the Exploratorium here: https://www.exploratorium.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/OTW_TH.pdf or ATJ

The bosun (a contraction of “boatswain”) was traditionally the crew member in charge of rigging and sails, and the bosun’s call vocabulary was originally centered on the manipulation of these technologies; technologies whose manipulation has figured regularly in Hawkinson’s work, most explicitly in the iris-like mandala of H.M.S.O. (1995), the repurposed dead Christmas tree Das Tannenboot (1994), and the self-explanatory Möbius Ship (2006). And these are just the tip of the iceberg—nautical references have been so prevalent in Hawkinson’s work that the project space Nyehaus, in New York, organized its 2007 survey show of his sculptures from 1993 to 2000 around this theme.

The bosun (a contraction of “boatswain”) was traditionally the crew member in charge of rigging and sails, and the bosun’s call vocabulary was originally centered on the manipulation of these technologies; technologies whose manipulation has figured regularly in Hawkinson’s work, most explicitly in the iris-like mandala of H.M.S.O. (1995), the repurposed dead Christmas tree Das Tannenboot (1994), and the self-explanatory Möbius Ship (2006). And these are just the tip of the iceberg—nautical references have been so prevalent in Hawkinson’s work that the project space Nyehaus, in New York, organized its 2007 survey show of his sculptures from 1993 to 2000 around this theme.

Instances of non-verbal musical languages and glossolalia also crop up regularly in Hawkinson’s work— Chipper All the Day (1993), Penitent (1994), Ranting Mop Head (Synthesized Voice)(1995), Tuva (1995), Barber (1997), and Pentecost (1999), each embody the disarticulation of the utterance from its discursive significance, simultaneously evoking the pathos of Babel and the transcendent Gift of Tongues.

But on a deeper level still, Bosun’s Bass exemplifies—in both its inspiration and execution—Hawkinson’s recognition of flawed translation as a fundamental generative process in human creativity, and particularly in his chosen field. More than any other artistic medium, sculpture can be seen historically as an act of direct (if allegorically mediated) transubstantiation—translating marble or wood into a human body, for example.

From Michelangelo’s finding and freeing the corporeal forms trapped in the stone and Donatello’s exhortations to his statue of Lo Zuccone (“Pumpkinhead”) to “Speak damn you, speak!” to the ancient tale of Pygmalion and even the 3 million year-old jasperite pebble resembling a human face discovered in Makapansgat Cave in South Africa—and thought by some scholars to be the earliest evidence of symbolic thinking in our genus’ history—figurative sculpture embodies the tragicomic hubris of man the creator’s feeble attempts to compete with God, or negative entropy, or whatever is keeping everything organized against all probability.

Faulty translation is a wonky central pillar to Hawkinson’s practice. “There’s something in the work about pattern recognition” the artist notes “—about seeing patterns in different circumstances and reusing them. I’ve talked before about misreading visuals—misinterpreting something and then working with that. Like here—” indicating 2007’s Leviathon, a gigantic skeleton that reveals itself on second glance to be made from a sculpted chain of rowing human figures “—mistaking the vertebrae in a brontosaurus in the Natural History Museum in London for Polynesian kayakers.”1

Many, many pieces from Hawkinson’s vast and variegated oeuvre exemplify this principle: fingernails into bird skeletons, eggshells into hands, boulders into bears, manila envelopes into clocks, feathers into motorcycles, water bottles into spinning wheels, pharmaceutical bottles, cupcake forms, aluminum foil, and plastic wrap into combination Maori mask/automotive headlights . . . you get the picture.2 Any crack in our certainty that things are what they seem can unleash a torrent of sensory and conceptual riches. That’s the Secret of Art.

Or one of them anyway. The disintegration of meal from menu at play in the jury-rigged linguistics of Bosunglish is entirely consonant with Hawkinson’s recombinant aesthetics. But the actual artifact he has produced adds several more layers of meaning, alluding to the history of the geographical location in which Bosun’s Bass was realized (the San Francisco Bay), focusing on specific characteristics and connotative asides of his chosen subject matter, and expanding on its interplay with his own body of work.

In chaining together a shipping container, the hinged bellows of an articulated bus, and a bicycle, to form a gigantic, automated version of a pivotal naval communication tool (and its operator), Hawkinson has stitched together an exquisite corpse of transportation technology, forging a capsule history of San Francisco as transit hub.

The bosun’s call itself is a totally obsolete control mechanism (dating back at least to the Crusades) for a mostly obsolete interface between culture and nature, sail and wind. The bicycle is a patently nineteenth century concoction, blithely ignorant of the petroleum-gobbling web of military-industrial shipping and handling that would follow in its dorky wake. It simultaneously evokes the earliest, most optimistic days of Modernism and its ongoing contemporary revival, more self-consciously rooted in a corrective urban utopianism whose ground zero is arguably the San Francisco counterculture of the 60s and 70s.

San Francisco as frontier outpost, as international port, as Gold Rush bed of hedonistic opulence, as silicon emerald city, as beat, hippie, queer ground zero, could easily be factored into this dissection. The city’s ahead-of-the-curve experimentalism as regards public transport (cue “The Trolley Song”) is brought to mind by the Bosun’s Bass’s flexible bellows made from the abdominal folds of an articulated bus (which made its American debut in the 60s via Oakland-based AC Transit), whilst the primary pulmonary automoton—the partially-submerged shipping container—consists of a twenty-first-century multipurpose cargo unit that morphs a little too smoothly between super-freighter, railcar, and truck (where’s Shia LaBeouf when you need him?!)—and is an omnipresent symbol of the trade deficit with the opposite edge of the Pacific Rim.

It is interesting to note how the elegance and complexity of the component technologies—from the invisible synthetic language and exquisite tendril-like simplicity of the bosun’s whistle to the ingenious self-sufficiency of the bicycle, to the unadorned squeezebox functionality of the bus bellows, to the brute rectilinear containment capacity of the shipping container—follows a kind of inverse evolutionary progression. Yet grafted together they suffer a sea change into something rich and strange—a robot monster running time backwards to issue a deep, mournful command— “Let go. Let go.”

Or was that “Pipe Down Hammocks?” I always get the two mixed up. Hawkinson’s piece may be just as easily interpreted as a celebration of technological progress as a critique. The humble shipping container is, after all, merely a single cell in an unfathomably vast complex trade organism which has afforded a certain percentage of our species a standard of living unparalleled in human history. Go Team Venture Capitalism!

In a much earlier work, Hawkinson literally encapsulated a comprehensive global history of transport by sealing an absurdly elongated mash-up of model kits into a snug bubble made from discarded plastic bottles. Trajectory (1995), radiates the uncanny—resembling a vacuum-sealed exhibit in an alien natural history museum, like a horizontal stalactite or filigreed mound of primate guano accumulated over a couple of millennia. A curiously inert artifact, the uniformly silver mutant extrusion of vessels-within-vessels conflates ancient sailing ships, tugboats, automobiles, airplanes, helicopters, jets, and spacecrafts (is that the X-15?!), rendering the technological narrative arc as a fait accompli: signed, sealed, and delivered. But this ain’t the case with Bosun’s Bass. It goes one step beyond.

Sometime in the very early 70s, a former Air Force electrical engineer named John Draper stumbled on a community of blind telephone hobbyists, who asked his help in developing an electronic tone-generating device to gain unauthorized access to various capacities of the phone system. The key frequency was 2600Hz, which, when played onto an open long-distance line, fooled the Phone Company into believing the caller had hung up, allowing said caller unlimited untraceable access to an open long-distance line. Draper and his fellow Bay Area “phone phreaks” discovered by chance that this exact tone was generated by an easily obtained plastic toy whistle from the bottom of a cereal box, and Draper soon took on his legendary nom de guerre, Captain Crunch. This was the birth of computer hacking.

After Esquire ran a highly publicized profile of Crunch and his phreak cohort, he was arrested for “toll fraud” and given five years probation. The article also brought Crunch to the attention of a pair of ambitious UC Berkeley geeks named Steve—as in Wozniak and Jobs—who enlisted Crunch as a tutor as they embarked on the entrepreneurial Hegira that would come to be known as Apple.

There’s a famous story about Crunch using the cereal-box whistle (which, incidentally bore no resemblance to the traditional opiumpipe shaped bosun’s instrument!) to telephone himself via a chain of long distance connections that circled the globe. I remembered hearing some of this a long time ago, but had forgotten about it until Bosun’s Bass jogged my memory. Improbably, the most archaic station in Hawkinson’s revised trajectory therefore links it to the next logical passage in post-industrial evolution, to the very technological reconfiguration of reality that rendered it obsolete: to the Digital.

There’s a famous story about Crunch using the cereal-box whistle (which, incidentally bore no resemblance to the traditional opiumpipe shaped bosun’s instrument!) to telephone himself via a chain of long distance connections that circled the globe. I remembered hearing some of this a long time ago, but had forgotten about it until Bosun’s Bass jogged my memory. Improbably, the most archaic station in Hawkinson’s revised trajectory therefore links it to the next logical passage in post-industrial evolution, to the very technological reconfiguration of reality that rendered it obsolete: to the Digital.

This probably (though not certainly) coincidental anecdotal association turned my mind to other facets of Hawkinson’s work, beginning with the cognitive mechanism of his latest monstrosity. The “brain” of Bosun’s Bass is the binary score carved into the rubber of the rear tire of the bicycle plus the relays that translate these bumps and troughs into the various channelings and closures that result in the desired musical communication. The bosun’s whistle is itself a binary instrument, its vocabulary based on combinatorial oscillations between high and low; fractally augmented by trills, warbles, and microtonal slurs, certainly, but piping an essentially Cartesian jig.

Although in this case I guess it’s more of a Leibnizian jig. Often referred to as the conceptual father of computer science and information theory, the seventeenth-century philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz was obsessed with binary numbers for most of his life, and eventually—after a very early exposure to the I Ching— formulated a theology of zero/one interplay between Creator and Void. All the riotous phenomena of creation generated by a dialectical engine of irreducible polarity, a piston stroke, the wind moving across the face of the water.

Sculpture as a negotiation of form and void is simultaneously the most obviously materialist and the most mysteriously metaphysical theoretical reduction. Leibniz himself, anticipating the scientistmathematician Benoit Mandelbrot’s discoveries in the field of fractal geometry by four centuries, denied emptiness, saying “matter presents an infinitely porous texture that is sponge-like or cavernous but devoid of empty space, as there is always a cavern within every cavern.”3 The apparent dualism of the I Ching is, in fact, a temporary polarity, and each extreme contains the most infinitesimal germ of its opposite, which triggers an instantaneous reversal. Now that’s what I call translation!

Tim Hawkinson’s Bosun’s Bass is, like many of his works, a sad and beautiful puppet designed to contain and exclaim such contradictions; a simulacral human figure pieced together from its own technological excreta, summarizing our journey thus far, and the whittling away of time and place as the binary gap between point A and point B, of here and there, is incrementally negated by the evolution of transport. Rising from the ocean which is the mother of all life on Earth, standing just west of the end of human history, breathed by the pulse of the Moon’s gravitational pull on our blood and our imagination. Hear its cry: “Hail! Haul! Hoist Away! All Hands! Pass A Word! Pipe Down! Let Go! Let Go!”

1 In conversation with the author, April 2007.

1 In conversation with the author, April 2007.

2 Respectively, Bird (1997); Fist (2009); Bear (2005); Envelope Clock (1996); Sherpa (2008); Orrery (2010); and Koruru (2009).

3 “Letter to Des Billettes, December 1696,” in Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Philosophical Papers and Letters, vol. 2 trans. and ed. and introduction by Leroy E. Loemker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), p. 77.

Doug Harvey is an experimental musician whose early turntable experiments led to his grounding. His book ‘patacritical Interrogation Techniques Anthology Volume 3 (AB Books, New York) collects historical and contemporary documents applying Jarry’s ‘pataphysical concepts to the deliberate procurement of Bad Intelligence. His “Outsider Theory” class taught at CalArts and elsewhere examines the suspicious similarities between Critical Theory and paranoid conspiracy writings. www.dougharvey.la www.dougharvey.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment