"Three hundred years ago, on June 24, 1717, four autonomous lodges of the philosophical/political underground that had inexplicably sprung up within the structure of the medieval architectural stone masons guilds met at the Goose and Gridiron Alehouse in the churchyard of London’s St. Paul's Cathedral, merged into what was to become the Grand Lodge of England, effectively launching the movement of modern Freemasonry. Antics ensued.

While even a cursory history of the Freemason phenomenon and its impact on the culture and politics of modern western civilization is beyond the scope of this essay, it’s important to cover at least some of the high points in order to convey exactly why the installation of Jim Shaw’s The Wig Museum in the repurposed Wilshire Boulevard Scottish Rite Cathedral constitutes one of the most appropriate and fruitful site-specific art installations of all time.

Since the 1970s, Shaw has been producing work that simultaneously explores the structure of various belief systems and the forms in which they manifest themselves, with a particular emphasis on the legion of vernacular twentieth-century media fallout—fliers, booklets, posters, album covers, knick-knacks, videos, and so on—which insinuate their ideological memes into the collective libidinal appetite. In this exhibition alone, he cites Abstract Expressionist collage cartoonist Ad Reinhardt, technology entrepreneur Steve Jobs, nineteenth-century French painters Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Théodore Gericault, Eugène Delacroix, visionary English book artist William Blake, political cartoonist Thomas Nash, modernist prankster Marcel Duchamp, Dutch proto-surrealist Hieronymus Bosch, beliked actress Sally Fields, Superman comic artist Wayne Boring, animator Walter Lantz, and science fiction author H. G. Wells. Among others.

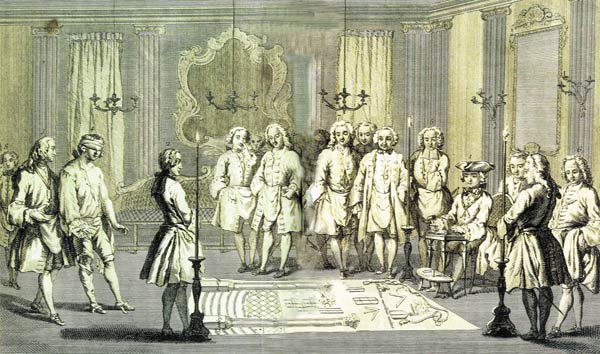

One of the most radical aspects of Shaw’s work is that he treats the belief systems and symbolic forms—the ideology and iconography—of capital-A Art with the same political and aesthetic equanimity and skepticism as he would, say, Scientology or the International Monetary Fund, although his scrutiny has most often been drawn to the elaborate cosmologies of fringe religious movements and secret societies like the Masons. Everybody knows that the intrigues of The Art World have more in common with Masonic convolutions than it likes to admit—constantly negotiating accusations of paranoia, defensiveness, and elitism, for example. Plus No Chicks Allowed!

Shaw’s oeuvre can be understood as a ferocious parody that vivisects the conventions of Western civilization’s moral and intellectual traditions in a language that mimics the convoluted and deliberately incoherent institutional mystification by which our imaginations are continually conquered and colonized. But these same strategies of semiotic hypersaturation can be seen in any number of esoteric spiritual and philosophical traditions whose stated purpose is to dislodge the initiate from their habitual understanding of the nature of reality in favor of a direct, unmediated experience—a denial-of-service attack on The Matrix.

The Wilshire Scottish Rite Masonic Temple was built in 1961 by Millard Sheets —as patriarchal figure in the history of Los Angeles art as can be imagined. Sheets, a regionalist figurative painter, headed the art department at Scripps College as well as Otis Art Institute, oversaw the Los Angeles County Fair’s then-prestigious annual art exhibit, and was in charge of which artists were hired to do murals for the Works Project Administration during the Depression. After the war, he entered the public sphere even more emphatically, setting up an architectural design firm that created idiosyncratic, modernist figurative mosaics for buildings from Washington D.C. to Honolulu, as well as the forty-two Home Savings and Loan Association Buildings for which he’s best remembered.

Oddly, Sheets was never a Mason, and when Judge Ellsworth Meyer approached him with the commission he asked for an explanation for undertaking such an extravagant project. As Sheets later recalled, they “had some very good thoughts about the new relationship of Masonry to society and why they felt this was an important time to build the temple and why they wanted to truly represent the spirit of Masonry.”

Whatever those “very good thoughts” were, they didn’t quite pan out, as membership in the Lodge—as in fraternal organizations nationwide—rapidly declined over the next several decades. By the early 1990s, the Wilshire temple was being rented out for commercial interests (in violation of its zoning parameters) and, amidst local complaints about parking difficulties and darker allegations, the 110,000-square-foot edifice was shuttered and cordoned off, becoming a notorious real-estate white elephant until the Marcianos came to its rescue..."

Read the rest of Puzzling Evidence: Jim Shaw VS The Illuminati in "Jim Shaw THE WIG MUSEUM" Marciano Art Foundation Project Series Issue no. 1, ISBN 978-0-9992215-0-1