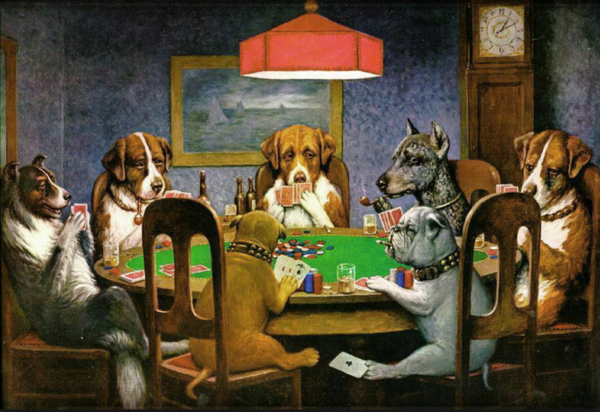

C.M. Coolidge, A Friend in Need, 1903.

The He-Man Action Movie Appreciation Society meets regularly to interrogate promising high-budget mainstream shoot-’em-ups in the context for which they were designed—big, loud movie theaters. The Society’s inaugural screening resulted in my report

“Is Jason Bourne a 123-minute Psychotronic Blipvert for Hillary?”, which ended with a pre-endorsement of

The Accountant—“a film that finally addresses the question ‘What if Good Will Hunting was a chick and Jason Bourne banged her and they had an inbred baby that was all like

Shine-meets-

Transporter and turns out to be the other guy from Good Will Hunting? Whoa.’”

This précis, though based entirely on the impressive trailer that screened before Bourne, is in fact a pretty accurate summation of The Accountant’s conceptual underpinnings. Ben Affleck is an autistic accountant who practices out of a strip-mall in suburban Illinois, but secretly jets around laundering money for drug cartels and terrorists. He knows kung fu and is a deadly marksman, because his dad was Special Forces. But the Treasury Department is onto him! J. Jonah Jameson sends his statuesque African-American data analyst to track Ben down, or else be exposed as the violent teenage vigilante she was! Antics ensue.

The H.M.A.M.A.S.’s most recent screening was actually John Wick Chapter 2, a film that received surprisingly positive reviews, many of which single out the impressive use of actual fine art in the art direction (not to mention the bizarrely Gilliamesque secret hitman telephone exchange!). My analysis of this cinematic milestone will be forthcoming, but I was particularly struck by the inert literalism of JW2’s fine art factor when compared to two brief pictorial incidents that raise The Accountantseveral notches above the herd.

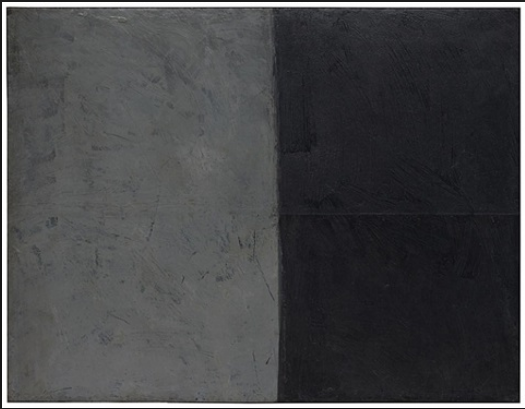

The first occurs when young Ben’s parents are visiting some hippie therapist’s autism ranch to see if he can help with their problem child, who sits in the common area working obsessively at a jigsaw puzzle. We don’t see it at first, but in a rapid sequence intercut with the parental consultation, L’il Ben starts going all “Judge Wopner!” because he can’t finish his task, until the resident neurodiverse cutie finds the missing piece and hands it to him. It’s at this point that we get our first actual look at the puzzle he’s working on—it’s a monochromatic gray rectangle, like a Brice Marden painting.

Pollock puzzle, collection Sam Erenberg

Which isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. In the early ’60s the Springbok company began issuing die-cut puzzles depicting abstract works by Kline, Krasner, Hofmann, de Kooning, and Pollock—whose Convergence was marketed as the most challenging puzzle of all time. Later in the decade, game companies upped the ante by manufacturing puzzles that were completely monochromatic—sometimes on both sides, though I doubt Brice ever saw a dime. And on the surface, the level of cognitive complexity required is what the blank puzzle signals to us about L’il Ben.

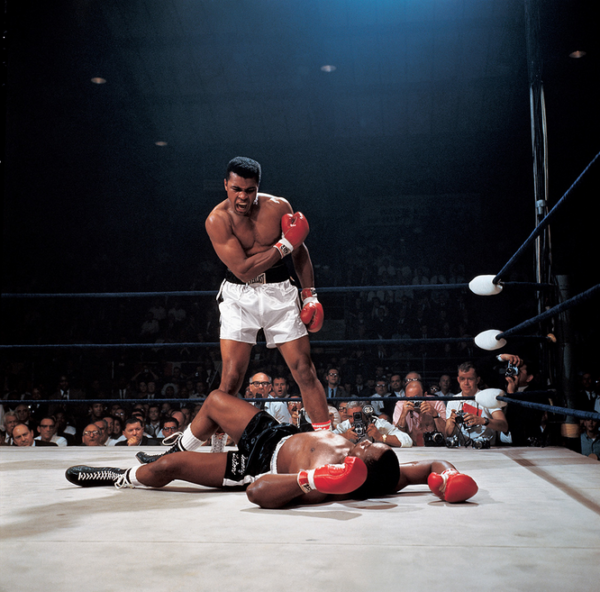

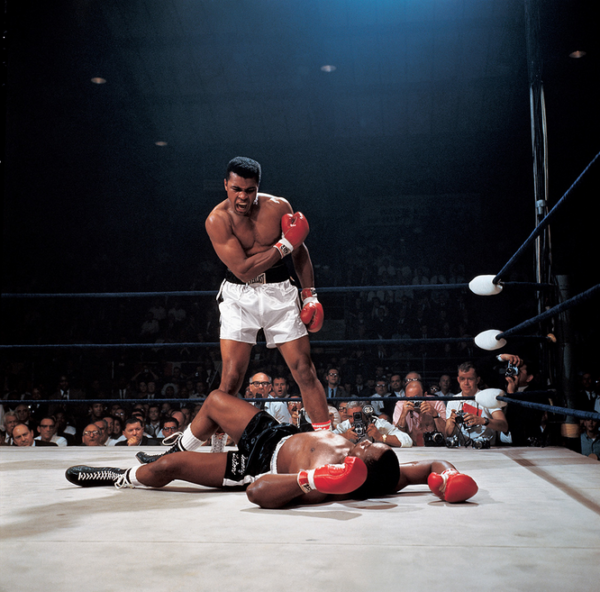

But just as he’s gratefully inserting the last piece to complete the non-image, the camera angle shifts radically, looking up through the glass table, through the gap in the blurry puzzle, framing L’l Ben’s bespectacled eyes. As he snaps the last module into place, the image snaps into focus, revealing that he has been assembling—upside down—Neil Leifer’s iconic shot of Muhammed Ali looming over the knocked out Sonny Liston in 1965. In a few seconds, the filmmakers have established a complex symbolic metaphor —the outsider warrior poet constructed in secret beneath a veneer of unparseable late-capitalist sang-froid; the Emperor card reversed—encoded in an equally (if more esoterically) loaded set of references to the production, distribution and valuation of 2D pictorial artifacts in contemporary culture.

Normally, if I perceive this sort of reference to Painting and its Discontents as coincidental—it’s just an upside-down jigsaw puzzle for God’s sake, not some dissertation on the tangled political and phenomenological relationship between photography, the avant-garde and kitsch. But The Accountant brackets its Revenge of the Asperger Ronin storyline with a second, even more explicitly art-historical sight gag, which is set up early, but delivered only in the tying-up-all-the-loose-ends montage—in fact the last shot in the movie before the hero rides off into the sunset.

We first glimpse grownup Ben’s art collection when he retreats to his secret storage unit holding his airstream full of currency, weapons and other tangibles—including a decent Renoir and—more improbably—a Jackson Pollock. And not just any Pollock, but 1946’s Free Form (mutated to more than double size), thought to be his very first drip painting. Ben must have done some real ugly shit for the Rockefellers to score that. So the whistleblower girl in distress is also an accountant, but one who wanted to go to the Art Institute, but Dad said “No,” and she makes an awkward friendship overture to Ben that includes an exchange on the merits of C.M. “Cash” Coolidge’s “Dogs Playing Poker” series. On the run from industrialist mercenary hitmen, she winds up in the trailer and is all like “OMG a Pollock original! You’re not like other accountants.”

Umm… spoiler alert, I guess. Once the antics are out of the way, she’s back at her modest flat and a mysterious package arrives, and here is the second incident. The package contains a stretched and framed canvas, which we see her unwrap and plunk down on her bed with a puzzled, then amused expression. The picture is Coolidge’s A Friend in Need (1903), probably the most famous Dogs Playing Poker image, whose central narrative detail of cheating is conspicuously cropped from our clearest view of it. Distress Girl’s expression goes frowny again, because she notices a surface anomaly in a corner of the painting, pokes around and actually tears away the Coolidge canvas to reveal the gazillion-dollar Pollock beneath. Both Ox and Self overcome, Ben heads off for his next adventure—Jason Bourne vs. The Accountant: The Treadstone Audit. Stay tuned.

How the World Looks to a Crazy Person