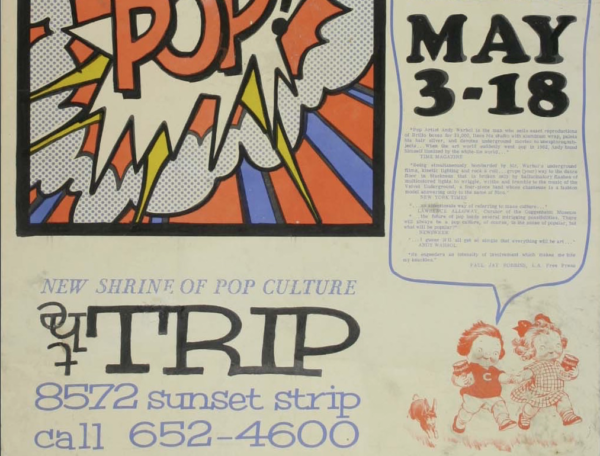

Fifty years ago—in May 1966—the Velvet Underground played their legendary West Coast debut at Hollywood nightclub The Trip as part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. On the first night, the joint was packed with curiosity-seeking hipster celebrities; Cher famously declared, “They will replace nothing, except maybe suicide.” But on the second night, the place was empty except for five people. One was Kurt Von Meier, a UCLA art historian who played a key role in the Red Krayola’s early career before writing a 350,000 word essay on Duchamp’s ball-of-twine readymade (it’s online!). The other four were also art world figures: Stanley and Elyse Grinstein and Sid and Rosamund Felsen.

If Rosamund had done nothing else after that night, I’d be impressed. But, as it turned out, she went on to found and operate one of the longest-running and most influential commercial art galleries in Los Angeles, representing, at one time or another, most of the major players to emerge in the ’70s and ’80s art world in LA and environs, including Mike Kelley, Chris Burden, Lari Pittman, Marnie Weber, Jim Shaw, Jeffrey Vallance, Karen Carson, Paul McCarthy, William Wegman, Alexis Smith, Chuck Arnoldi, Erika Rothenberg, Meg Cranston, Pat O’Neill, Jason Rhoades, Laura Owens, Kim MacConnell, Steve Hurd… you get the picture.

The other side to Rosamund’s superstar stable was the equally compelling roster of idiosyncratic artists’ artists like Richard Jackson, Jacci Den Hartog, Steven Hull, Nancy Jackson, Jimmy Hayward, Marc Pally, Tim Ebner, Jean Lowe, Pat Nickell, Pauline Stella Sanchez, Grant Mudford (Rosamund’s spouse) and M.A. Peers (my spouse). Because of M.A.’s nearly 20-year association with the gallery (and my own friendship and professional association with a number of RFG’s other artists), I got a pretty good insider’s view of Rosamund’s modus operandi.

Contrary to many horror stories I’ve heard about other local contemporary dealers, Rosamund is unconditionally supportive of her artists’ creative autonomy, and their need to develop and experiment over time, regardless of sales. Once she is convinced of an artist’s merit, she trusts their vision. She has an excellent eye, an open and curious mind, and a very individualistic sensibility, which allows her to champion artists with unlikely or unfashionable ideas or styles. Rosamund also has a strong and confident instinct for elegant and aesthetically sophisticated exhibition design.

All four of the buildings that RFG has occupied have been remarkable exhibition spaces in their own right. The legendary first space on La Cienega Boulevard had previously been the home of Riko Mizuno and Gagosian galleries, and was the site of many landmark exhibits— including Burden’s Big Wheel (1979) and Kelley’s Monkey Island (1987), including his stuffed animal magnum opus More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid.)

Rosamund had kind of stumbled into the gallery business. That night at The Trip, the Felsens and Grinsteins were in the very first stages of establishing Gemini GEL, the ambitious commercial fine art printmaking shop that played a significant role in LA’s ascendency as an art world player in the ’60s and ’70s. Rosamund began as the shipping clerk, but was operating in a curatorial mode by the time she left in 1969 over disagreements with master printer Ken Tyler. She moved over to the Pasadena Art Museum, where she was registrar and curator of prints until Norton Simon’s hostile takeover spelled the end of that institution’s golden era. Rosamund was preparing to go back to attend UCLA when a casual acquaintance named Timothea Stewart needed help running her new gallery on La Cienega Boulevard.

That first show with Timothea was a labor of love devoted to the late Wallace Berman. Rosamund sat behind the desk. The exhibit closed after five months with no sales, and Timothea apparently decided she had played her one good hand and was ready to fold. But suddenly everyone was going “Rosamund, you should take over and open your own gallery.” And she was all like ”Who me?” But then she was all like “Why not?”

After a dozen years, RFG moved to an even bigger, more beautiful gallery—the former Santa Monica Boulevard studio of photographer Tom Kelley, who had taken the Marilyn Monroe nude calendar photo. Inspired by the paintjob on contractor (later gallerist) Frank Lloyd’s pickup, she had the building painted yellow, which eventually inspired Jason Rhoades’ career-making Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts (1994) installation.

McCarthy’s “Bossy Burger”

Felsen continued staging landmark shows such as McCarthy’s “Bossy Burger” and Jeffrey Vallance “Presents The Richard Nixon Museum” (both 1991), but the art-market crash led her to relocate to Bergamot Station, and an exodus of her star artists to dealers who were more inclined to participate in the emerging global art supermarket. Rosamund’s vision seemed to grow more personal, and she began taking on more woman artists, including non- (or neo-) Angelenos like Joan Jonas and Mary Kelly.

About a year ago, as Bergamot imploded, RFG made an ambitious leap of faith to a newly remodeled space on Santa Fe Avenue, but the art world being the seething vortex of poisonous psychic vampirism that it is, couldn’t support the new venture. Early this summer, it was announced that the next show at RFG would be its last—in its permanent physical space anyway. RFG will continue to represent many of its artists, maintain a virtual presence online, and rematerialize as needed for whatever pop-up or art fair opportunities present themselves. (Which may be the new default mode for art galleries.) But Rosamund’s always been ahead of the curve. What was her assessment of the proto-punk feedback drone pioneers The Velvet Underground back in the summer before the summer of love? “Terrific.” Take that, Cher!

No comments:

Post a Comment